| S u b m a r i n e S a i l o r . c o m | ||

| Loss of the Stickleback

SS-415

Pat Barron EN2 (SS) USN

1957-1961 :

I joined the Navy in the summer of 1957, went to boot camp in San Diego and then directly to Submarine School at New London as a Seaman Apprentice. I was ordered directly to USS Stickleback SS-415 out of Submarine School. Stickleback was a Squadron 7 boat. The skipper when I went aboard was a “mustang” Lieutenant Commander by the name of Hugh Knott. When he left he went as commissioning skipper of USS Grayback SSG-574. He was relieved by Lieutenant Commander “Dutch” Schulz who was the skipper when Stickleback went down. Stickleback was in the yards when I went aboard so the qualification program was really slowed down. I was within a month or so of qualifying when she went down. Would you believe I had to start all over again on USS Wahoo SS-565 when I went aboard her after Stickleback?

After we got out of the yard we went to Tahiti on shakedown. We were the second American warship to go to Tahiti since 1945. Wahoo had been there about eight months before. We had a 10-day transit to Tahiti. We ran several drills every day and qualified new watchstanders to fill out the underway watch sections. We ran every kind of drill you could imagine until our responses were automatic. What really stuck in my mind were several of the submerged Silent Running drills. We would stay down for a couple of hours with everything turned off and the boat would get really hot. I have never been that hot! The condensation was just pouring down the bulkheads and off the pressure hull and on to the deck. We had rags down everywhere to soak up the condensation. The crew was stripped half naked and the sweat was just pouring off you. God it was really hot! Going across the equator was quite an experience. Over two thirds of the crew were pollywogs. The skipper decided to cross the equator submerged and backing down because it had never been done before. Then we surfaced and had the ceremony on deck. The shellbacks had been saving slop from the galley and rigged up chutes full of the stuff on deck we had to crawl through. First we were blindfolded and ran a gauntlet of shellbacks that paddled our ass. Then they cut a two-inch wide cross through our hair with barber clippers. It left your hair in 4 quarters after they were done. The shellbacks gave us condoms filled with olives you had to suck on then they rubbed your face in King Neptune’s greased belly. Finally when the ceremony was completed we rigged a fire hose topside and everyone got washed down. We had 10 days alongside in Papeete Tahiti. It was a Polynesian backwater in 1958. No tourism to speak of, one airplane flight in and out per week. The main drag through Papeete was a dirt street with board sidewalks. I was Maneuvering Watch Starboard Lookout when we came into the harbor. I was looking through binoculars at the beach off to starboard as we pulled in and I couldn’t believe my eyes. The women on the beach were half naked! There were a lot of officials and a band on the pier to meet us. After we tied up and put the brow over a lot of visitors came aboard, a lot of them were Tahitian women with armloads of leis. They would put a lei over our heads and kiss us. I was topside standing next to our Chief Engineman “Pappy” Rail. I said to him, “holy shit Pappy, these women don’t have any clothes on!” And he said to me, “This is going to be one hell of a liberty for you guys!” and it was! The pier where we tied up looked right down the main street of Papeete. I had the duty the first day in port. I had the 2000 to 2400 topside watch that night. You know how the weather is in the tropics. We had a torrential downpour that night. While I was on watch, I saw one of our division riders headed back to the boat in this downpour. When he got to the brow he was soaking wet and his white uniform was all muddy from the knees down from walking in the mud of the street and boy was he is drunk, I mean paralyzed! He made it over the brow to the boat, staggered a few steps toward the Escape Trunk then just collapsed in a pile on the deck. I called the Section Leader and he got the Duty Officer who came topside. The Duty Officer took one look at this guy and says, “Have the Below Decks Watch get a torpedo cover from the Forward Torpedo Room and just cover him up. He is to big to move.” He was still lying there, in the rain, under a torpedo cover when I got off watch at 2345. I gave the gun to my relief and went ashore. I walked right down the street from where we were tied up to a bar called “Quinn’s Tahitian Hut.” I had a couple of drinks there, met a girl and got laid. That night there was no one on the boat except the Section Leader, watchstanders, Duty Chief, and Duty Officer. By the end of the fourth day no one had any clean uniforms left with all the rain and mud. By then the guys were going ashore in anything including Sarongs and t-shirts. I swear, it was like some South Seas movie! There were more women aboard the boat than guys in the duty section. I mean the women were sleeping in the after battery! You would go into Hogan’s Alley and there would be a woman sleeping in your bunk! The beer was something else, it was called Hinano Beer. It was green beer and it would give you the shits, everyone had the shits from it. We couldn’t even depart on time. When we mustered on sailing day, half the crew was missing. We were supposed to sail at noon, and we finally got underway at about 1600 in the afternoon. It took a couple of days just for everyone to recover. The skipper was in his rack for the first three days underway. He was a mess; the stewards threw some of his clothes over the side because they were so filthy. After he recovered and was up and about, he started holding Captains Mast for all the offenders. We had over 30 Captains Mast’s on the way back for the guys who showed up late for duty days or didn’t show up at all for duty days, and missing muster on sailing day. That was my first foreign liberty port and even with two WesPacs on Wahoo, I never saw another one like that. Well as you can imagine, after a couple of weeks of underway drills, crossing the equator, a 10 day liberty in Tahiti, and a 10 day trip home to recuperate, the crew had really grown close. Just listening to all the stories about the liberty in Tahiti, listening to the Tahitian music on the 45 RPM records on our juke box in the crews mess, (I don’t have a clue who bought the records in Papeete) and hearing who was restricted and who got busted at Captains Mast, really gave you a sense of being a tight crew. I don’t think the effects of that liberty really began to wear off until we were about 2 days out of Pearl Harbor. After shakedown we started regular operations. I stood helm, lookout and planes watches underway and topside watches in port. Daily ops, or out for two-maybe three days and then back in. We made a weekend trip to Nawiliwili Kaui, and one to Lahina Maui where we anchored out. We had dungaree liberty there. You have to remember, this was the late 50’s, Hawaii was still a territory, and it was before the jet age and all the tourism that we know today. About 75% of the crew was single; our hangout was Bill Lederers on Hotel Street, or the Dolphin Club on Beretania Street. I had been aboard about seven months, I had passed the test for Fireman and I was about a month away from qualifying. We were doing our final local underway before leaving for WesPac. The Chief of the Boat Vern Atha put Mike Fallet and me on mess cooking the day before our last underway. The morning we got sunk Mike and I started mess cooking. We were in the After Battery when we got underway that morning. We were just going out for the day to provide ASW target services for the USS Silverstein DE-534. I remember it was right before noon meal, we were submerged and we lost power and took a tremendous down angle and started going down. Emergency lights went on and shortly after that I heard them start blowing main ballast tanks. The blow went on for a long time and we started to run out of air. EN1 (SS) Leon Mungerson was Auxiliaryman of the watch and was on the blow manifold. He put the Captains Air Bank on service and it was the damnedest noise I had ever heard. I thought the boat was exploding. He did not equalize pressure slowly; he just slammed the Captains Air Bank stop valve wide open. There was a WHAMMMM as the relief valve lifted. It was the loudest noise I had ever heard! Once we got the down angle off and our descent stopped the next thing that happened was we started going to the surface in a hurry. (I was told later we went to 700-800 feet before recovering.) I think there were eight of us in the After Battery at the time. The next thing we heard was “ALL HANDS FORWARD!” over the 1 MC, and then about a minute later we heard, “TUBES AFT, CONN, LOAD AND SHOOT ONE RED FLARE” over the 1 MC. (I heard later the red flare was not fired because the Torpedoman on watch had gone forward when the word was passed for all hands to lay forward.) Then the Collision Alarm sounded. I don’t remember who shut the water tight door between the Control Room and the After Battery. Then we hit the surface and within like about 30 seconds we were rammed by the Silverstein on the port side right at the bulkhead between the Control Room and the Forward Battery. There was a hell of a CRASH and shock from the collision. It shoved the boat to starboard and knocked all of us down. I remember after the crash I got on my feet and pulled the collision/flooding bill out of the bill holder. We then rigged the After Battery Compartment for collision/flooding. I looked through the dead light in the watertight door and the water was rising fast in the Control Room. All I could see was cork floating. I was thinking OH GOD THOSE GUYS ARE DEAD! You know how they say your life passes before your eyes at times like this, well it happened to me. I can remember to this day picturing my girlfriend from high school. I also remember telling Paul Duxbury not to worry we would get out alive. About four maybe five minutes after the collision the word was passed on the 1MC, “ABANDON SHIP” and we headed aft through the Engine Rooms, Maneuvering Room and into the After Torpedo Room. The Chief of the Boat Vern Atha had been in the After Battery compartment with us when we got hit. Now he was handing out life jackets in the After Torpedo Room when we got there. All the compartments were empty as we went aft. Even the Electricians in Maneuvering were gone. We were the last out from our end of the boat. One of the things I noticed after I got topside was USS Sabalo SS-302 coming towards us in the distance. A third class Torpedoman dove in the water and started swimming towards the Sabalo. I will never forget the fear I saw in that mans eyes, I thought he was on the verge of panic. I didn’t have much respect for him after that. Sabalo picked him up a few minutes later.

Immediately after the collision the guys in the Control Room, Sonar, and Radio escaped through the Conning Tower and dogged the lower hatch after the last man was out. Remember I told you that right after we blew the ballast tanks the word was passed on the 1MC for all hands to lay forward, well there were eight guys in the Forward Battery on the way to the Torpedo Room at the time the Collision Alarm sounded. The watertight door to the Torpedo Room was shut and dogged at the time of the collision and they were trapped in the Forward Battery as it was flooding. Now I heard afterwards from one of the cooks who was trapped in the Forward Battery that he could see through the deadlight in the watertight door that one of the officers in the Torpedo Room was holding the dogging handles and wouldn’t let them out. The guys in the Forward Battery were all yelling and screaming, “OPEN THE DOOR LET US OUT OF HERE!” Somebody in the Torpedo Room pushed the officer aside, opened the Watertight Door and let the eight guys out then shut and re-dogged it. The guys trapped in the Forward Battery were really pissed about what happened to them and the Cook told me he was so angry he could have killed the officer who was holding the door shut. If they hadn’t got out of the Forward Battery when they did they probably would have died, if not from drowning then from Chlorine Gas as the battery cells flooded with seawater.

Silverstein was holding her bow in the gash, Sticklebacks bow was still dry, and everyone in the Forward Torpedo Room went out through the Escape Trunk Hatch and made their way aft of the sail. So there we were, all hanging on topside waiting for direction on what to do next. Later, when Silverstein backed out of us the boat took on a port list and started down by the bow. USS Greenlet ASR-10 arrived and came alongside to starboard and tied-up next to us. Leon Mungerson and one or two other guys were up forward trying to hookup air hoses from Greenlet to the External Salvage Air fittings to put air into the boat. Our skipper had the Greenlet provide a SCUBA rig for Mike Fallet (he had just completed SCUBA school a couple of weeks before and was the ships diver) and had him go over the side to inspect the damage. Fallet dove down to the bottom of the boat, went into the ballast tank through the flood port, looked over the damage and saw the Wardroom curtains dangling out of the gash in the pressure hull. After that he went back out through the flood port, climbed back aboard and reported what he saw to the skipper. Mike Fallet had a big set of balls that day! What a Sailor! It wasn’t to long after that that the skipper ordered most of the crew to board Greenlet and that’s the last time I was aboard Stickleback. The last message sent using Stickleback’s call sign was actually sent from Greenlet. It reported latitude and longitude of the boat, all crew survived, and loss of everything except pay records. I don’t know how they got the pay records off in that they were kept in the yeoman’s shack in the Forward Battery Compartment. A Third Class Quartermaster took the Deck Log with him when he abandoned ship. Oh yah, somebody also got the Battle Flag off the boat during Abandon ship. Leon Mungerson was one of the Stickleback old-timers; he put her back in commission in 1951. He was aboard over 6 years when the boat went down. He had been aboard the longest. He was a true diesel boat sailor. He was an Auxiliaryman and he knew the boat inside and out. I can still picture him today up on the bow of the boat after Silverstein pulled out of us and Greenlet was alongside, hooking up external salvage air hoses. He was soaking wet and looked like a dying man. Maybe it was because of what he had just gone through, maybe it was fear he was going to loose the boat, his home, like it was for all of us. I can still remember it, the boat continued to sink lower and lower by the bow until water started lapping up the front of the sail. That’s when the skipper finally left the boat and came aboard the Greenlet. The boat continued to sink lower and lower and finally she went over and the stern went up with the screws, rudder, and stern planes sticking out and then she was gone. The other long serving Stickleback sailor was a First Class Steward, and I don’t remember his name. After the boat went down and we were on the Greenlet, Mungerson was soaking wet, and he and this Steward were hugging and crying. There were the longest serving sailors on Stickleback and they had lost their home. We had about a two-hour run back to Pearl, all of us on the fantail of the Greenlet, it was early evening with one of those great Hawaiian sunsets. We were all standing, sitting, and lying huddled together like beaten dogs. It was pretty sad, almost like a movie with that Hawaiian sunset. When we got in we tied up by Subbase Repair. Our Chief Engineman by the name of “Pappy” Rail, (He was a WWII Submarine Veteran, had a Purple Heart Medal from being wounded on USS Sealion SS-195 during the attack at Cavite and made a bunch of war patrols on USS Sailfish SS-192 during the war.) was standing at the head of the brow and shook every mans hand when they left Greenlet. From there almost everyone went to the chapel. After the Chapel service Subbase opened up “Small Stores” for us because we had lost everything when the boat went down. After getting clothes from “Small Stores” we went to our berthing area in the Barracks. The only direction we got that night was, “you can have liberty, just don’t talk to the press.” A lot of us went to Bill Lederer’s that night and got good and drunk. The next day we had a meeting at the Barracks. We got chow passes for the Subbase Enlisted Mess, and we were given “dream sheets” to fill out. We were told we would be temporarily assigned to another boat. That’s when three guys “Non-Vol’d”, one was an ET that was 6 foot 7 inches tall and the other two were my classmates from Submarine School. Then they had us fill out a claim form for our lost uniforms and personal Items. There were a lot of rumors and wishful thinking on our part like, the Navy will pull a boat out of mothballs for us, stuff like that. It was really hard on us, the Stickleback crew, as we began to realize over the next few days the Submarine Force wasn’t going to keep us together. We were like brothers; I mean the crew was really tight! People just didn’t realize how hard it was for us loosing the boat. After all the work in the yards, the shakedown to Tahiti and the work-up for WesPac, she was our home and we were proud of her and what we had done. I don’t think anyone but another submariner can understand how close the crew gets and how much the boat means to you. There was a Court of Inquiry at the Submarine Base on the loss of the boat. I wasn’t called and I didn’t attend. I did hear that Leon Mungerson was a key witness and gave very emotional testimony. I heard he ended up getting a commendation. I never did understand why Mike Fallet didn’t get more recognition for his dive into the ballast tank that day. I mean if he had done today what he did in 1958 the Navy would have given him the Navy Cross. Anyway, we all got commendatory remarks on our evaluations. We were all concerned about what was going to happen to the skipper. As it turned out he made out OK. After the Court of Inquiry we gave him Stickleback’s battle flag. I think it was probably after the Court of Inquiry that it finally sank in that the Stickleback crew was no more. We were assigned to Squadron Seven awaiting further orders. We still went ashore together but it felt different because we were all going to different boats. Most of the guys stayed in Pearl Harbor as I did. I got orders to USS Wahoo SS-565 along with three of my shipmates, a First Class Torpedoman, a Second Class Engineman and a Seaman. Wahoo was at the tail end of a WesPac deployment so for the next six weeks I was assigned TAD to USS Tunny SSG-282, USS Sterlet SS-392, USS Blackfin SS-322, and USS Gudgeon SS-567, until Wahoo returned to Pearl. I would go out for daily ops then back in at night. I didn’t stand any watches or anything. The only funny thing that happened during that time was I got a big boil on the base of my spine. When the doctor looked at it he asked me if I had been on the Stickleback. When I told him yes he told me the reason for the boil was nerves. There is still camaraderie among Stickleback Sailors. I remember one time when I was on the Wahoo the USS Catfish SS-339 was in port on the way to WesPac. I was out on the pier and I heard someone calling my name. “Hey Barron” I turn around and it was “Dutch” Schulz. He was skipper of Catfish. It just seemed so normal at the time. He asked me how I was doing and where I was, so I told him I was doing fine and was on the Wahoo. I asked him how he was doing and he told me fine and that one of the Stickleback Engineman was aboard Catfish with him. He told me the Court of Inquiry cleared him but he knew that he wouldn’t go any higher than Captain. There is always that link with my Stickleback shipmates because of the shared experience of that day. I still have dreams about the Stickleback. You know we were really lucky. I think today, how the hell did we get out of that situation with that much water coming in? We owe a lot to the CO of the Silverstein because he kept the bow of his ship lodged in us and slowed the flooding.[Website editor's note: The total number of crew/survivors was 82.] |

||

|

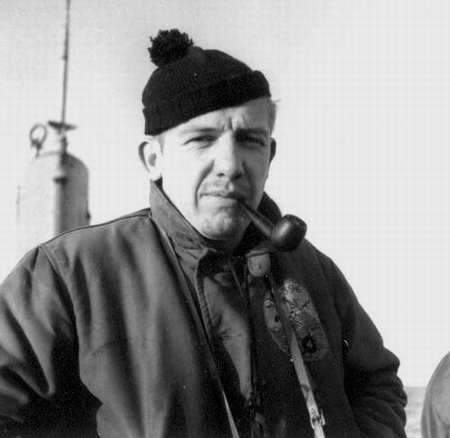

Credits: Pat Barron: Pat Barron served on USS Stickleback SS-415 and USS Wahoo SS-565. Following his naval service he work for 35 years in retail meat marketing and retired at age 55. He lives in Hayward California and is a member of USSVI Mare Island Base and is a Relief Crewmember with the San Francisco Chapter of USSVWII. Patrick Meagher is a retired Chief Torpedomans Mate (submarines). He has been collecting oral histories of post WWII enlisted submariners since 1993. Patrick can be found working onboard the San Francisco based museum submarine USS Pampanito SS-383 three days a week. He is a life member of USSVI Cuttlefish and Mare Island Bases, and an associate member of the Fresno Chapter of USSVWII. He lives in Sunnyvale California. Collision photos from USS Current website, Jim Vasko Other photos of Captain Shulz (during his time as XO on the Torsk) - thanks to Gil Bohannon for the heads-up on these photos.

Download the original MS Word document. - Published 2/2003 - |

||